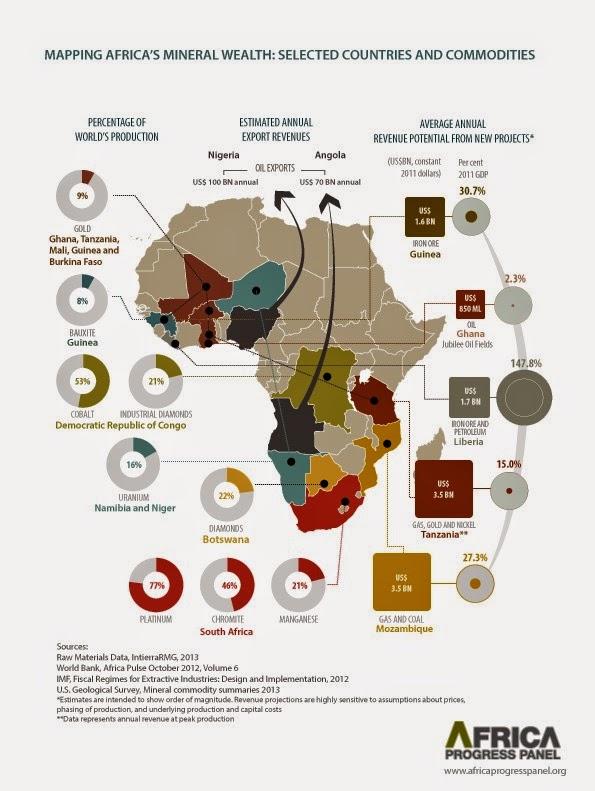

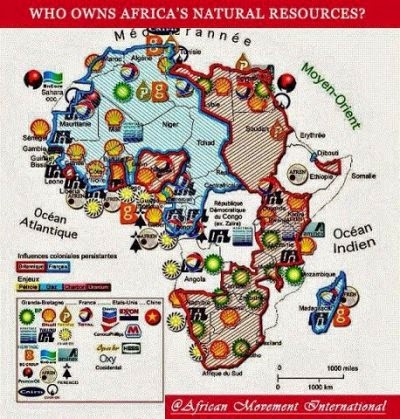

In the 19th century, foreign explorers came to Africa in search of ivory, rubber and free labour. Today, they come for Africa’s minerals — its copper, zinc and tungsten. The developed world needs them for its skyscrapers, cell phones and much in between.

The exchange is almost always unfair. Often, African governments don’t know the value of the natural resources underground, but mining companies from the West -and, increasingly, China -do. That knowledge asymmetry has cost African countries and their citizens as much as $1.4 trillion over the past 30 years.

But a more level playing field may be in sight, thanks to a World Bank initiative that aims to compile Africa’s mineral maps into a single, public database: the so-called Billion Dollar Map. The alleged goal is to give African nations as much information as possible about their natural resources so that they can earn a fair price for the minerals they sell, World Bank officials claim.

While mineral maps of the African continent exist, most are private or piecemeal. The Billion Dollar Map is crucially different: Its contents will be available to the public. And that, experts hope, will minimize underpricing and corruption, and help governments get a fairer price for their countries’ resources.

“When a government licenses its acreage for mining companies, they really don’t know what’s underground,” says Paulo De Sa, the World Bank geologist in charge of the project. “The mining companies know what the true potential of these minerals is, and the government doesn’t have a clue.”

African government efforts to force mining companies to process minerals before export may backfire as they come up against weakening commodity prices and investor demands that mining firms reduce risky investments. In the last year alone, Zimbabwe, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Namibia, South Africa and others have hinted at, announced or put in place measures aimed at adding value to minerals exports, which would boost tax revenue, encourage the formation of new businesses and add jobs. Zimbabwe, which holds the world’s second-largest platinum reserves after South Africa, has taken a hard line. Late last year, President Robert Mugabe threatened to stop exports of raw platinum in a bid to force mining firms to process the metal domestically.

Most developed countries already have mineral maps. Canada, for instance, has a geological survey of the entire country, which was compiled using exploration statistics from each province, and whose findings are publicly available online. In Europe, 29 countries are finalizing plans to produce a geological map of the entire European Union. Even Afghanistan has had its minerals mapped from the air by the U.S. Geological Survey.

While private mining companies have been mapping Africa’s minerals for decades, nations with mining interests have entered the game, too. France launched a similar, though less ambitious, program a decade ago, and a consortium of European and African countries recently undertook another . With Chinese firms’ stake in Africa’s minerals growing fast, the Chinese government last year reached a memorandum of understanding with Kenya’s government to spend up to $70 million on aerial mineral surveys across Kenya .

To create the public minerals map and database, the World Bank will first compile historical data on Africa’s buried minerals dating back to colonial times, such as old mining reports and maps like this one of Kenya from the 1960s. As the data is gathered, the compilations will be turned into publicly available PDFs.

Then researchers will use satellites to georeference the data, identifying proper coordinates for mineral discoveries marked on outdated maps. All this geodata will be combined into a central database so that researchers, and anyone else, can see which regions have not yet been explored.Next comes the process of filling in those gaps. Though it will be long and expensive, methods have much improved since the rudimentary maps of early 20th -century explorers.

By cutting some of the risk associated with mineral exploration, the map is also likely to accelerate mining across the continent, according to people familiar with Africa’s minerals sector. “It become really risky when you drill, drill, drill and don’t find anything,” De Sa says. That’s why mining companies tend not to invest unless they’re confident they’re likely to find large-enough mineral deposits. The Billion Dollar Map may help companies more quickly reach that confidence threshold.

That, in turn, would generate more revenue for African governments in need of new income sources to finance their development. “Even a small mine could create a couple thousand direct jobs in the area,” says Graham. “And that’s not even thinking in terms of potential infrastructure, and so on.”

[By: Jacob Kushner, http://www.africanglobe.net/]